Picture the scene: a group of men crouch around a campfire, roasting a freshly skinned dog, poking at the glowing embers with sticks.

They are barefoot and naked except for loincloths. Their backs and arms are covered in tattoos celebrating the human heads they have hunted.

This scene isn’t being played out in the tribe’s homeland in the mountains of Luzon, but in New York. And the Filipinos are, quite literally, a human zoo: the summer’s biggest attraction at Coney Island.

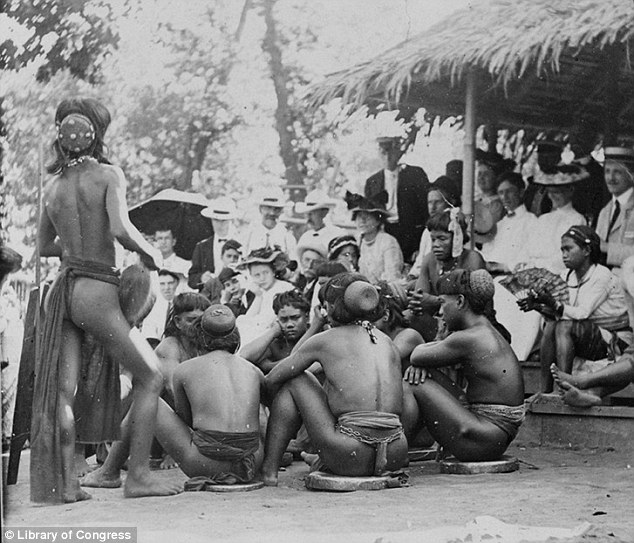

On the other side of a bamboo fence, crowds of families dressed in their Sunday best for their visit to Luna Park wait impatiently in line. They hand over their quarters and surge inside.

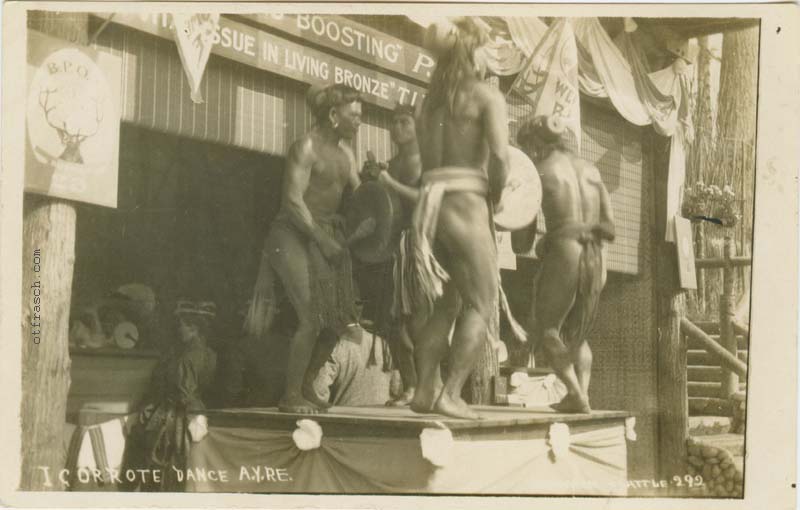

There they stand in open-mouthed wonder, as the chief begins to speak in a growling voice. The other “savages” start to chant, before breaking into a wild dance accompanied by gongs and drums.

The owner and creator of the village, Dr Truman Hunt, was the consummate showman. He dared visitors to get as close as possible to the fearsome dog-eating headhunters.

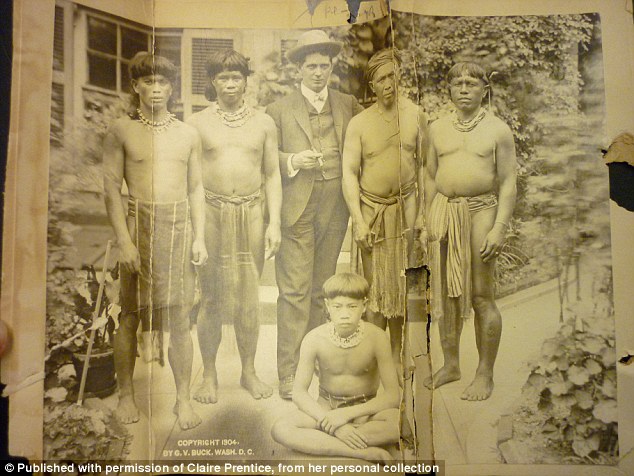

The Bontoc Igorrotes — known in America simply as Igorrotes — were the talk of the town in 1905.

Reporters from The New York Times, The Washington Post and even Vogue interviewed the showman and his tribespeople. They were visited by all the top stars of the day, prominent anthropologists and even Alice Roosevelt, the president’s daughter. They were, at that time, perhaps the most famous human beings in the world.

However, their rise to fame was just the beginning of the Igorrotes’ story. They would end up testifying against their former controller in an American court, being dragged around North America, getting lost in Europe and inspiring the lawmakers of the Philippines to amend the country’s anti-slavery laws.

Hunt first met the Igorrotes when he went to the Philippines to fight in the the Spanish-America War in 1898.

After winning control of the country, the USA began classifying its various communities, according to how ‘civilised’ or ‘savage’ they seemed. The Igorrotes, with their near nudity, headhunting and dog eating habits quickly captured the imagination of their colonial masters.

After winning control of the country, the USA began classifying its various communities, according to how ‘civilised’ or ‘savage’ they seemed. The Igorrotes, with their near nudity, headhunting and dog eating habits quickly captured the imagination of their colonial masters.

Hunt, who had served in the medical corps, was made lieutenant governor of Bontoc and became a trusted friend of the tribes.

Then, in 1904, the US government decided to bring 1,300 Filipinos from a dozen different tribes to the St Louis Exposition. The reason was political — by exhibiting the ‘savage’ tribespeople, the government hoped to win support for its colonial policies. “Look at these people,” they were saying, “how could they possibly govern themselves?”

Hunt was put in charge of the St Louis Igorrote Village. The Philippine Reservation was one of the most popular features of the fair and the Igorrotes were the undoubted stars.

Recognising their huge appeal, Hunt came up with a plan. He would return to the Philippines and gather his own Igorrote “tribe” and become a human zookeeper.

In Manila, he put his proposal to Dean Worcester, the colonial secretary of the interior, and one of the most powerful men in the Philippines. Worcester, perhaps recognising the propaganda value of the plan, loved the idea and readily agreed.

Hunt hired a young Filipino named Julio Balinag to act as recruiter, assistant and translator. Balinag had been in the original St Louis “tribe” and was ambitious and educated. During his first visit, he’d fallen in love with America and dreamed of moving there with his wife, Maria.

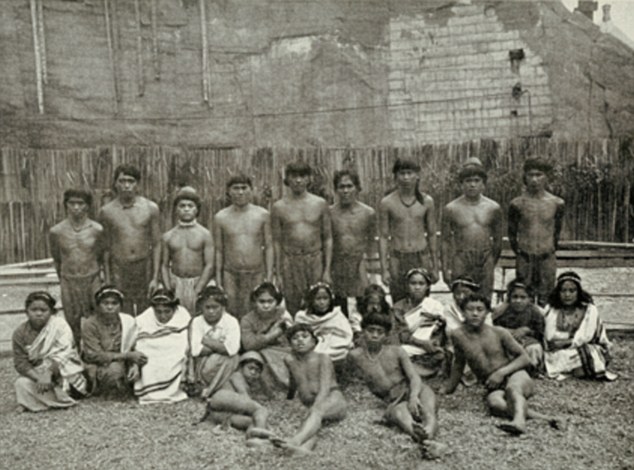

Hunt offered $15 a month to every man, woman and child who agreed to go to America. This was a life-changing sum for the Filipinos of those days. Hunt was inundated with volunteers and selected 50.

The oldest member was a man in his 60s named Falino Ygnichen; the youngest was a tiny seven-year-old orphan called Friday Strong.

From the moment the Igorrotes were installed at Coney Island, their every waking moment was lived out under the gaze of the public. When the crowds finally left each day at midnight, the Igorrotes were locked inside their bamboo enclosure.

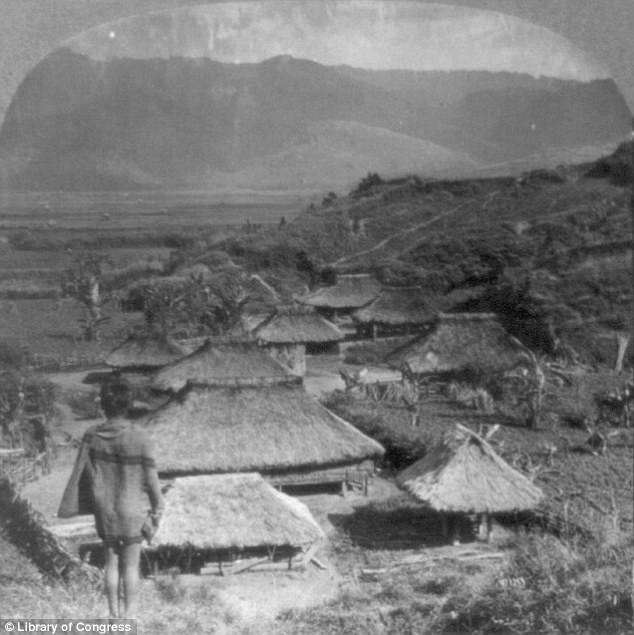

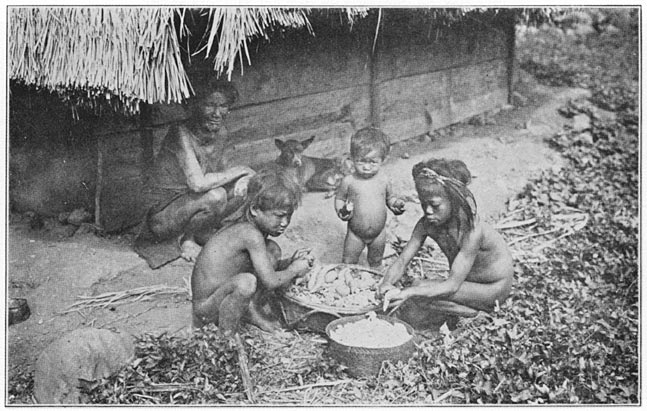

Their village was made up of thatched huts that they built themselves using straw, mud and bricks. The huts were cramped and dark, with dirt floors.

Every day, thousands thronged to see the “wild men and women” up close. They watched wide-eyed as the scantily-clad tribespeople began to sing, dance and feast on dog meat.

At home, the Igorrote only ate dog on special occasions, such as at weddings and after successful head hunts. But on Coney Island the dog feasts were so popular with the punters that the tribe were made to eat the meat every day.

To keep the crowds interested, Hunt insisted the village held mock weddings and phoney funerals. The men also conducted sham battles and recreated their head hunting expeditions.

As the weeks passed, the Igorrotes’ fame spread across America, attracting crowds from far and wide. Many well-meaning visitors brought gifts for the tribespeople, such as “decent” clothes for the women, candy for the children and cigars for the men. Some even offered to adopt the youngsters.

It soon became normal practice for the crowd to throw nickels and dimes into the village as a sign of appreciation.

Hunt had these scooped up daily, telling the tribespeople he was “keeping them safe” for them. He also collected the entry fees and took cash earned from the souvenirs that the Igorrotes’ made.

By the height of the summer, the tribespeople had made Hunt a very rich man. He and his wife, Sallie, dined in New York’s finest restaurants and were seen in all the best clubs. Sallie was just 18 — less than half Hunt’s age — and he spoiled his young wife with lavish gifts of fine clothes and expensive jewellery.

At the end of August, Coney Island welcomed the arrival of its first Filipino baby. Hunt was delighted. His tribe had made it into the pages of newspapers all over the world— the showman felt invincible.

However, Hunt did not have the Igorrote business all to himself. In 1905 another group of tribespeople had arrived in America with another Spanish-American war veteran (and former cigar salesman) Richard Schneidewind.

The two men couldn’t have been more different. While the flamboyant hunt seemed to regard his Igarrotes purely as just a commodity, Schneidewind, whose Filipina wife had recently died in childbirth, apparently treated his tribespeople like family, often inviting them to his home for meals.

Schneidewind took his Igorrote exhibition group to the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon, then on to Chutes Park in Los Angeles, where they were a huge hit.

Hunt was furious, and split his tribespeople in to three groups to maximise profits. This caused great upset among the tribesmen. Even those who weren’t related had developed strong bonds and relationships within the village.

Hunt’s groups toured the country, making dozens of stops, lasting anything from a few days to several weeks. This increased the distress of his tribe, as their already makeshift village was forced to become increasingly shoddy as they constantly moved from place to place, rebuilding as they went.

The rivalry between Hunt and Schneidewind was intense. In May, 1906, Hunt and Schneidewind ended up at competing parks in Chicago. The two showmen did everything they could to undermine each other’s exhibits.

Hunt rubbished Schneidewind to the newspapers, while Schneidewind wrote to the government. His letter reported that the village operated by Hunt was in a terrible condition. The 18 men and women, he wrote, were crammed into three small A-frame tents in a muddy scrap of land beneath a roller coaster.

A member of the public — perhaps encouraged by Schneidewind — also complained that Hunt’s Igorrotes were living in squalor. There were also rumours that Hunt had stolen the tribe’s wages, and that two men had died, without being given a decent burial.

In response, the Bureau of Insular Affairs sent in one of their agents, Frederick Barker, to investigate the claims.

When Hunt received a tip-off that the bureau was on his tail, along with a group of private eyes from Pinkerton’s legendary agency, he went on the run, taking some of the tribespeople with him.

A manhunt followed as Pinkerton detectives, the government agent, creditors and a woman who accused Hunt of bigamy pursued the showman across America and Canada.

Hunt kept one step ahead for months, until, finally, in October 1906, he was arrested for stealing from the Igorrotes. He was sentenced to 18 months in the workhouse after a sensational trial in Memphis.

With his rival out of the way, Schneidewind continued his career as human zookeeper. In 1906 he returned to the Philippines to collect another Igorrote group and embarked on a second tour of America. A third tour followed in 1908.

In 1911, he looked farther afield, and took a group of 55 Igorrotes to Europe. There they exhibited in France, Scotland, England, the Netherlands and Belgium.

However, for reasons that remain unclear, the tour wasn’t a great success. In 1913, after two years on the road, Schneidewind ran into financial difficulties.

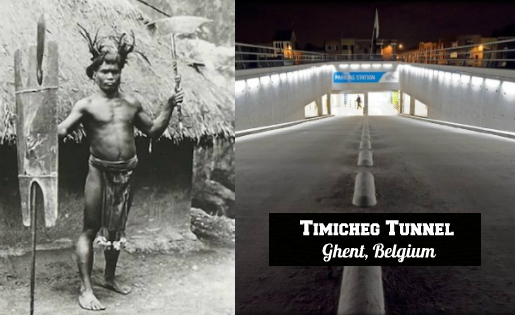

What happened next was similar to the denouement of Hunt’s tour. According to American newspapers, in the winter of 1913 a group of starving Igorrotes were found wandering the streets of Ghent, Belgium.

The group’s interpreters wrote to President Woodrow Wilson begging for assistance. In their letter, they complained that they had not been paid for many months and reported the deaths of nine members of their group, including five children.

Regardless of these damning claims against him, Schneidewind asked the Igorrotes to continue touring Europe until the 1915 San Francisco Exposition, with the promise of a handsome pay-off. Despite the hardships they had endured, about half of the group agreed. A sign perhaps that Schneidewind’s troubles owed more to incompetence than to cruelty.

However, fearing another scandal, the US government was unwilling to give Schneidewind another chance and decided to intervene. In December, 1913, the US consul in Ghent escorted the tribespeople to Marseilles, France, where they were put onto a boat back to Manila.

After they had returned, the Philippine Assembly took action and, in 1914, amended the country’s new Anti-Slavery Act to ban the public exhibition of Filipino citizens abroad.

At that point, the Igorrote zoo business came to an end. Although it is little remembered today, there is evidence to be found in Ghent, which named streets and tunnels after the tribesmen.

Throughout their many ordeals, it is reported that the Igorrotes always conducted themselves with tremendous dignity. This was despite the most outrageous provocations.

When considering the story of the Igorrotes, it’s impossible not to reflect on the question: Just what is civilisation, and what is savagery?

Comments are closed.